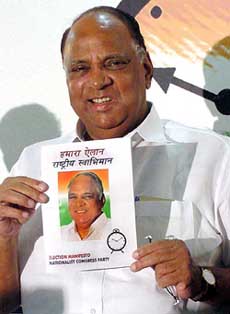

It is the evening of October 12, 2004 and Baramati's narrow market square, Bhegon Chowk, is overflowing with farm hands who have come to hear their hero, Sharad Pawar, speak.

He will address his sole election rally in Baramati today. The people of Maharashtra will go to the polls to elect a new government the following day.

Pawar's candidate will win. That is tradition. Pawar never campaigns in Baramati.

In Beed, not very far off, the then Bharatiya Janata Party state unit president Gopinath Munde, Pawar's keen rival, is also addressing a rally. He is promising the people that he will turn Beed into Baramati -- if they give him their votes.

In Beed, not very far off, the then Bharatiya Janata Party state unit president Gopinath Munde, Pawar's keen rival, is also addressing a rally. He is promising the people that he will turn Beed into Baramati -- if they give him their votes.

Baramati, in Maharashtra's sugarcane belt, has been a star constituency through most of Pawar's six terms in the Maharashtra state assembly and five terms in the Lok Sabha.

He has been the chief minister of Maharashtra for seven years and is the minister for agriculture in the present central government.

Over the last 30 years, money was poured into Baramati to make it the showpiece of Pawar's political ascendancy. It was designed to be proof of Pawar's identification with the humble farmer and his problems. Baramati was planned as a model for rural development.

The backbone of these development initiatives are the sugar cooperatives, which Pawar has systematically taken over. His brother, Appasaheb Pawar, was managing director of Baramati Sugar Cooperative through which Pawar has wielded much of his political influence.

The milk cooperatives, the horticultural cooperatives and the market associations are all controlled by Pawar and his men. He controls the money coming into Baramati, and the access to that money through his hold over the district cooperative banks.

"In Baramati, Sharad Pawar is likened to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. He is a man of great foresight. He has planned for Baramati keeping in mind the changes that will take place in the coming 20 years," says Milind Sangi, a Baramati local.

The prime minister himself praised Baramati for being a model for rural sustainabilty. The 'Baramati pattern' reads like a planner's dream come true.

The agriculture-based system has education at its heart. It is supported by industrial production and is bolstered by profitable agri-businesses, horticulture and animal husbandry initiatives.

Or at least, that is the scripted story. The other story shows a struggling town in Maharashtra's Marathwada region. Even the presence of a political heavyweight such as Pawar has only marginally alleviated the harsh conditions of life in this perennially drought-hit land.

Only a third of Baramati is irrigated. The other two-thirds, where more than half its population lives and farms, is dry and dependent on rain.

Little has changed for the small-farmer here in the last 15 years. He still cannot afford to plant sugarcane, which requires large amounts of water. He grows wheat, jowar, bajra and seasonal vegetables, which are not profitable.

The 100-km road from Pune to Baramati is dry and the vegetation, where it patches the scenery, is not a relief to the eyes. But 5 km out of Baramati, the promise of green pastures seems to materialise.

Well-stocked shops in newly built shopping complexes and Internet parlours dot the widening road at regular intervals. Shiny-new streetlights stand out luridly like new money in a settled township.

You look for rows of tall-standing sugarcane stalks. Instead, there are small, fenced-off plots growing other crops. It is mid-May and the sugarcane has been cut.

But not much sugarcane was planted here this season. Ramdas Chowdhar, a small farmer in the canal-irrigated belt of Baramati, who plants sugarcane on 1.5 acres of his three-acre plot, says he didn't plant any during the last two years of drought.

"We would have starved without poultry and dairy farming," he says.

Officials at the Malegoan Cooperative Sugar Factory reveal that from an average of 800,000 tonnes a crushing season, they've dropped to 270,000 tonnes this season.

"Farmers planted only one third the sugarcane, as a result of which sugar prices have increased," says A M Pisal, managing director of the sugar factory.

Sugarcane yield in Baramati has dropped by as much as 30-40 per cent during the last five years.

According to agricultural scientists at Krishi Vigyan Kendra, a non-governmental organisation headed by Pawar and funded by the Indian Centre for Agricultural Research, the average sugarcane yield in Baramati has dropped from about 60 tonnes an acre to between 35-40 tonnes.

Infestation by the wolly apheid and salination of the top soil are cited as the main reasons for the drop. "Earlier, profit margins used to range between Rs 15,000-20,000 an acre, now small farmers find sugarcane plantation unprofitable," says S V Karange, an agronomy scientist at KVK.

The Krishi Vigyan Kendra is part of an agricultural trust controlled by Sharad Pawar. The 110 acres of land under the trust are used for the demonstration of new technology, hybrid seeds and high-yielding varieties of sugarcane, grapes and other crops.

KVK works with the local farmer to develop water conservation, weed-control, fodder management and salination control techniques. This is the second stop on Baramati's guided tour.

The first stop is the sprawling, 150-acre Vidya Prathisthan campus set up by Pawar in 1972. The campus has grown from having just commerce, science and arts colleges to include BEd and MEd colleges, an information technology institute, a bio-technology institute and an engineering college on 150 sprawling acres.

Says Sushma Chaphalkar, the director of Vidya Prathisthan's bio-technology institute, "The idea was to provide a secure environment where the local farmer wouldn't hesitate to send his daughters."

The campus is self-contained with modern buildings, gigantic playgrounds and uninterrupted green patches. The college buildings are airy and have superb infrastructure.

The offices with their lace and damask furnishings are limmed with money.

The IT institute is empowered with a fiberoptic backbone, two dedicated lease lines from Reliance and wi-fi connectivity. The colleges, hostels and staff quarters on campus have their own telephone exchange.

The bio-technology college accepts students from all over India, and has been ranked the second best private bio-tech institute in India. "Vidya Prathisthan Campus has induced a change in the texture of society that is reflected in the standard of living and awareness of the people," Chaphalkar says.

However, Pawar has had his share of detractors who claim that the campus has been built at the cost of a few thousand crores, with a large part of the money not coming from Pawar's personal wealth or from his party funds but from an industrial house that has been in the news for its feuding brothers.

Industry is just picking up in Baramati. At the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation site in Baramati, the Italian automobile maker Piaggio has set up a plant.

Kalyani Pipes and Bilt Grapics are the other industries here. It is not much, but the other tehsils in the Baramati parliamentary constituency -- Indapur, Daund, Purnadar, Shirur, Haveli -- don't even have this.

Wine-making came to Baramati much before wineries were set up in Nashik and Narayangaon. The Baramati Grape Industries Limited owned by United Breweries makes wine under the Bosca brand name.

It set up shop here in 1975 and crushes about 5,000 tonnes of grapes per annum. The grapes are sourced from a 10 mile radius and has 500 farmers in the supply chain.

However, a much larger portion of the grapes grown in Baramati are exported. According to Sunil Pawar of the Baramati Fruit Growers Association, between 13,000-14,000 acres in Baramati is used for growing the seedless Thompson White meant for table purposes.

Eighteen containers of Thompson White were exported this season (each container roughly contains 400 kg), according to Pawar. He says the prices this year touched Rs 68 a kg.

The profit margins for export quality grapes range between Rs 100,000 to Rs 500,000 an acre, according to him.

However, the initial cost of grape farming being prohibitive, not all farmers can afford to grow grapes. Pawar himself admits that only five out every 100 farmers grow export quality grapes.

While not all farmers grow grapes, most sell milk to their local cooperatives in Pawar's constituency. The presence of the Dynamix dairy farm (owned by Britannia Industries previously and now acquired by Schreiber) in Baramati has assured the local farmer that his milk will be purchased.

Milk production in Baramati has gone up from a mere 265 litres a day in 1970 to over 200,000 litres daily. Haribhau Tawre, the managing director of the Baramati Milk Cooperative says, " It is due to the efforts of Appasaheb Pawar that cross-breeds such as Holstein Friesen were introduced to Baramati."

Most farmers and their tenants today own two cross-breed cows in Baramati, ensuring them cash from the sale of milk if their crops fail.

There is, however, a catch even in dairy farming. Farmers like Chowdhar say that they do not get the money from selling milk on a daily basis.

Payments are made on a fortnightly basis and during times of drought, a small amount on a daily basis could come in handy.

Pawar's critics claim that while Baramati has become the hub of development, in Daund and Indapur and other tehsils, development has stagnated.

In Daund, which is just a 20 km drive from Baramati, 36 villages have been struggling with drinking water problems. In Indapur, 22 villages have been having reeling under severe water shortage for drinking as well as for irrigation.

In Baramati itself, the civic administration was unable to handle an outbreak of 1,000 jaundice cases about a month ago after the drainage pipelines leaked into the city's drinking water supply line.

Though the epidemic claimed only one person, it showed up chinks in the city's civic amenities.

Baramati is grid with every switch controlled by Pawar and his family. "When dignitaries such as Manmohan Singh and Lalu Yadav come to Baramati, they are shown Vidya Prathistan, KVK and the developed parts of the city. They go away impressed, but nothing has changed for the poor people who don't plant sugarcane," says a local.

It is too early declare the Baramati pattern a hoax. But neither is it the land of milk and honey that the Prime Minister's statement seems to suggest.

However, the people are enterprising and hard-working. They take pride in the Baramati dream that it will be to Pune what Pune became to Mumbai a couple of decades ago.

The truth? As the cliche goes, it is what serves the best interests of the most. Baramati is no exception.

| Farming emus in Baramati

Discussing emu reproduction on a sizzling Baramati afternoon, squeezed in between a visit to an agricultural trust and the Malegoan sugar factory, it is easy to imagine oneself in the middle of a Beckettian adventure. Sandeep Tawre, a young entrepreneur from Baramati, who gave up his poultry business to start an emu farm, says he read about a childless couple who conceived after going on a diet of emu eggs. He says sperm counts have been known to go up by 72 per cent on regular consumption of emu eggs. Tawre started the farm in 2000 with 100 pairs of the bird brought from Australia. Three years of research on the Internet had shown him that there was a sizeable market for emu meat, and that it was sold for as much as Rs 1,750 per kg in America and Japan. He says that the amount of emu meat consumed on an average daily around the world will only go up once it known that emu meat is 78 per cent fat free. He uses the contract framing model perfected by the poultry business. He has given out his 100 original birds along with chicks to farmers around Baramati for rearing. The eggs, when they are laid, are brought to Tawre's farm where they are hatched. The chicks are once again given out in a ratio of two females to one male for rearing. The male birds are used for meat. He owns all the birds, and the farmers are provided with the feed for the birds and given handling charges for looking after them. He says there is between Rs 8,000-10,000 to be made for every bird, and since the emu is capable of laying eggs for up to 30 years or more, the business model is self-sustaining. Hello, testing. . . live from Baramati 90.4 FM is a dedicated community radio station that caters to farmers in a 35-km radius in and around Baramati. The programming in is Marathi, and airs interviews with agricultural experts, local success stories and entertainment. The three-month-old station is broadcast for four hours in the morning, and telecasts are repeated in the evening. Vidya Prathisthan's Institute of Information Technology (VIIT) is in charge of running the station; however, the programming is outsourced from Krishi Vigyan Kendra. The station has a team of three presenters who broadcast live from a studio on the campus. The cost of running the station is budgeted at Rs 20 lakh (Rs 2 million) a year and is funded through a World Bank contribution of Rs 4.5 crore (Rs 45 million) for e-education programmes run by VIIT. Amol Goje, director of VIIT, hopes to extend the programming time to showcase local talent and even expects to sell some of his programming to other radio stations. |