The Rediff US Special/Aseem Chhabra

Kanwal Rekhi came to the United States a few decades ago. And before he made his first million dollars, he did odd jobs to support himself, including working in a restaurant. After he got his green card, Rekhi sponsored his siblings to join him in the US.

made his first million dollars, he did odd jobs to support himself, including working in a restaurant. After he got his green card, Rekhi sponsored his siblings to join him in the US.

Now that he is reportedly worth $ 500 million, Rekhi is using his high profile to start a debate on US immigration policies. However, his desire to scale back the family reunification clause -- the cornerstone of US immigration -- has not gone well with South Asian community activists.

It also did not help that Rekhi in an interview with rediff.com said the family reunification clause had resulted in "poor quality" immigrants, i e, "taxi drivers and non-professionals" entering this country. His concern is these "secondary immigrants" could result in a backlash against the rest of the Indian immigrant community in the US.

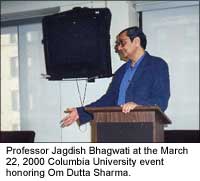

"This is an elitist position that flies in the face of America's historical commitment to taking in the world's 'huddled masses' and its deep seated ethos of fairness and justice," Professor Jagdish Bhagwati, Arthur Lehman Professor of Economics at Columbia University, said. "Uniquely, the US has committed itself to familial values and to only a limited preference for skilled immigrants, making economic calculation not the only criteria for admissions."

Professor Bhagwati welcomed Rekhi's interest in the immigration debate, but added that even on economic grounds it was not easy to figure out whether a skilled immigrant was more beneficial to the US than an unskilled one.

"Is one more Indian doctor working on Park Avenue, New York, where doctors are in ample supply, doing more good to the American natives than a Haitian peasant woman who works as a maid and enables women in New York to go to work because their homes and children are taken care of?" he asked.

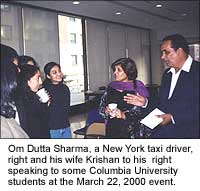

Last year, Professor Bhagwati and his wife Padma Desai, G & R Harriman Professor of Economics at Columbia University organized an event to honor a 66-year-old New York taxi-driver, Om Dutt Sharma, who in 1997 opened a school for girls in his village in India. Later this month, Sharma will receive an honorary doctor of humane letters degree from Mount Holyhoke College, a premium women's school in South Hedley, Massachusetts.

"Was this 'poor quality' immigrant not a better example and inspiration to us, to American natives, indeed to all humanity, than anyone from India in Silicon Valley or on our campuses?'' Professor Bhagwati asked. "I hope the Immigrant Support Network and Rekhi make a case for more visas for their members, while extending their embrace, not their scorn, to the unskilled, even the illegal, immigrants from India."

Sreenath Sreenivasan, associate professor of journalism at Columbia University, supported Professor Bhagwati's view it is wrong to say that some immigrants were better than others.

"Too many Indians work from the presumption that there is a good kind of Indian that should be in America and I disagree with that vehemently," Professor Sreenivasan said. "We forget there are a lot of Indians in America who are being left behind and we have to look out for them. There is nothing saying that an engineer from a certain town in India is a better immigrant than someone else."

"Either you are in favor of immigration or you are not," he added. "I don't think we should be selective and who are we to make this moral judgement. All kinds of people are needed to make a country. And you can't make it just on the backs of doctors or engineers or whatever."

Other community activists, including Chaumtoli Haq, an attorney at the Asian American Defense Fund, also welcomed Rekhi's plans to get involved in the immigration debate.

"For a long time we -- those of us who do community work, have been encouraging entrepreneurs to put their resources towards community issues," Haq, who is also a member of the community group South Asian Action and Advocacy Collective, said.

"But while we commend him, we think he should not reinforce certain classicist and racist assumptions about our community about low wage workers. When such words are spoken by a member of our community, it can have a damaging impact."

Haq said people like Rekhi held a false belief that low wage workers like taxi drivers were uneducated. In fact, she said often taxi drivers in cities like New York were highly educated, but were denied jobs in their professions due to their accents, foreign degrees or religious beliefs.

Bhairavi Desai of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance seconded Haq's views.

"Most drivers in New York are highly educated, but because of the underlying racism in this country, working class people are not allowed access to other labor markets," Desai said. "They work harder than higher income people. But unfortunately they do not have access to the resources that high income people do."

"Collectively, they service a million people a day," Desai said, referring to the yellow cab drivers in New York City. "And when we talk about livery cab and limousine car drivers, gas station attendants, and restaurant and construction workers, all of them are essential and the backbone of the economy of this country."

She thought it unfair that Rekhi was able to sponsor his family members to migrate to the US, and now he would like to see the family reunification clause of the this country's immigration policy abandoned.

"He has the right to his own family, but why should those who are the working class and poor suffer loneliness and isolation in this country simply because of their class," she said.

Desai also disputed Rekhi's comments that there was a backlash against the Indian community largely because of what he believes to be the presence of "poor quality immigrants".

"People in power are responsible for the backlash, not people that are powerless," she said. "They are victims of the backlash. I think he (Rekhi) has his pyramid of power turned upside down."

Andrew Kashyap, an attorney with the National Employment Law Project and a colleague of Haq at SAAAC, quoted Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank, as saying the US economy was dependent on the supply and a pool of cheap immigrant labor.

"Whether it is a white collar sector -- the H-1B worker to the cab driver, the restaurant worker and the domestic worker, whether you are a high skilled worker or a low skilled worker -- you are at the mercy of your employer," Kashyap said.

"The way the laws were designed by Congress and the INS, it puts the power in the hand of the employer, both for H-1B workers and for low skilled workers," Kashyap added. "And these laws do not provide for adequate protection for immigrant workers rights. We should be cracking on body shoppers (temporary employers of H-1B visa workers), instead of curbing the migration of low skilled workers."

Parag Khandhar of the Asian American Federation of New York -- an umbrella group representing 36 social service and advocacy groups -- also said there was practically no difference between highly skilled H-1B visa workers that Rekhi is now going to represent and the low skilled immigrants like taxi drivers. Rekhi recently joined the board of the Immigrant Support Network, a group that lobbies for the rights of high tech H-1B visa workers.

"Make no mistake, but they are all indentured labor," Khandhar said. "We need to cross the class lines and see this is something that happens to H-1B visa workers and the farm laborers. They are filling the need and then they will be sent back."

"He (Rekhi) needs to open his eyes and realize that all immigration is a poor quality immigration. I think there is general fear among people who have made it in this country and who come from this angle, that if too many people come here, their social standing and maybe their immigration status will be challenged."

Khandhar speculated that often successful Indians in the US felt threatened by the fact that no matter how many millions of dollars they might have, they are still immigrants.

"So it becomes instead of brother do you need a hand, brother can I shut the door behind myself so that you can't get in," Khandhar said.

Rekhi's success as well that of other Indians in Silicon Valley has given them access to top politicians in this country, Khandhar said. Last year, for instance, some top Indian honchos in Silicon Valley held a fundraiser for Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore.

"But it is personal access which their money gets them," Khandhar said. "It's not the community access that some of us advocates on the ground level are working towards every day. There is power that comes with money, no doubt. But there is other power as well. And when we are able to put them together is when our community will actually start to make an impact on this country. But these statements really hurt that cause."

Another academician, Vijay Prashad -- assistant professor of international studies at Trinity College at Hartford, Connecticut -- spoke out against Rekhi's comments that a six-year visa, the maximum term for an H-1B visa worker, is not temporary enough. In fact, Rekhi said that the US should design a simpler temporary visa.

"Most of us who have contacts with H-1B workers know they are against the very idea of a temporary visa," Prashad said. "If you are bringing in people on H-1B, you are bringing them for the most productive part of their lives. Have the decency to let them have their lives as well."

Some H-1B programmers would want to return to India, but that decision should not be made by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, he said.

"My position is you are taking young people away from their dream when you bring them for six years," Prashad added. "Then the American dream is a post-dated check. I am giving you the check now and it is gone in six years."

Back to top

Tell us what you think of this feature